Rosemary’s Baby. Carrie. Even The Babadook, if we want to go modern. Mothers and motherhood in horror films tend to get a bad rap. Meanwhile, you don’t have to look very hard to find examples of good fathers in horror films. Most men of the genre are there to protect their families from demons, ghosts, and killers who haunt the night. They are the protectors, not the monsters. Even in films where fathers are portrayed as anti-heroes or antagonists, they have noble motivations. There are exceptions, but overall, mothers are monsters and fathers are heroes.

The very act of motherhood — carrying a child — is a source of horror for many films. The transformation of the physical form that comes with motherhood is ripe ground for horror films. After all, there’s something growing inside you, draining nutrients from your body to eventually be birthed into the world. Isn’t that the plot of a horror film on its own? But in these films, motherhood itself is seen as a transformative way to turn good women into something else, or allow bad women to become even more monstrous.

Take Rosemary’s Baby, the seminal monstrous motherhood classic. Rosemary turns into the mother of the Anti-Christ, and soothes her baby to sleep at the end of the film. Her agency has been stripped away over the course of the film by every other character, including her husband. Motherhood becomes an invasive act – one where she slowly loses her bodily autonomy and herself, as her offspring becomes her entire identity. Not only does she lose her sense of self, but pregnancy warps her entire body, giving her strange cravings and changing her physiology, turning her into a shadow of herself.

Another classic, Carrie, depicts motherhood as being monstrous, even though the pregnancy is long since over. Carrie’s mother is a vicious, religious fanatic who abuses her daughter, damaging her psyche irreversibly and forcing the girl into a state of isolation. Her fervor and brutality make her more of an antagonist than the cruel students who torment Carrie. Indeed, it is the scene of Carrie murdering her mother that provides audiences with the most catharsis, and not that of Carrie murdering her fellow students. The mother is the true monster in the film, more so than the telekinetically gifted Carrie or her vicious peers.

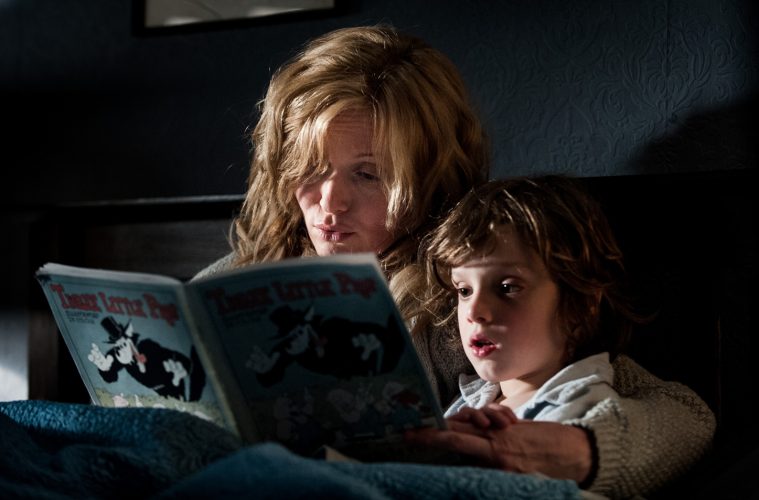

Even films centered on mothers as protagonists put them into a corner. Take The Babadook, a recent film that focuses on a mother and her child. One reading of the film is that the Babadook itself represents the mother’s ableism and inability to deal with a child who displays symptoms of autism. The monster that drives Amelia, the protagonist, to the brink of disaster and an unthinkable act, is a representation of her darkness and dislike for her own offspring, who she is raising alone following the death of her husband. It is hard to talk about the film without giving spoilers – indeed, it’s new enough that the spoiler statute of limitations still applies – but watching the film through this lens of a mother’s inability to accept her child adds a new level to it.

On the flip side, there are very few films that make fathers out to be the monsters under the bed. Fathers are rather heroes, anti-heroes, or men with noble motives, despite their wicked deeds. They are the protectors, the defenders, and the heroes of their stories. Even in films like The Amityville Horror, in which father figures are possessed by demonic forces, they are able to drive out their demons through strength of character or love for their families. In films like It Comes At Night, their cruel deeds are done in the name of family and love, not hatred or brutality.

Maybe this is because fatherhood comes with less of a transformative physical aspect, but maybe it all comes down to good old-fashioned misogyny, since horror films have historically been unkind to women. From virginal final girls to the torture porn subgenre, scary flicks tend towards a deep-seated hatred of women, and indeed violence towards them. It makes sense that this violence is then transferred into the twisting of motherhood as a transformative and evil state, while fatherhood is considered a noble role.

There is another kind of motherhood that has become popular. This mother starts off the film as a poor caretaker and then either sacrifices herself to prove her goodness or must find a way to save her child, and in doing so, learns that motherhood is the ultimate goal. Consider the recent indie horror film The Monster, in which a mother – a terrible parent by any standard – is forced into the role of protector and sacrificial lamb during she and her daughter’s encounter with the titular beast. These mothers are substandard and oftentimes presented as disasters. They are afforded a little more respect, however, than the average horror movie mother. They fill the same role as a father does and become the protectors.

There is no easy way to solve this problem without delving into the roots of the genre and how it often exists to punish women. However, it’s important to keep this trope in mind while enjoying the latest scares at the box office, and writers should remember it as they work on their newest horror ventures. In doing so, they could breathe new life into a genre that’s too often mired in dated tropes, and provide a fresh take on gender roles in film.