Every generation gets its own version of Nancy Drew. In the 1930s, that was Nancy, Original Flavor: an opinionated, adventurous sixteen-year-old sleuth whose lawyer father diverted cases her way. A few decades later, those original books were revised for a new generation, removing racist language and streamlining convoluted plots. Nancy aged to eighteen and became a little meeker—still poised and confident, but quicker to smile politely than question authority.

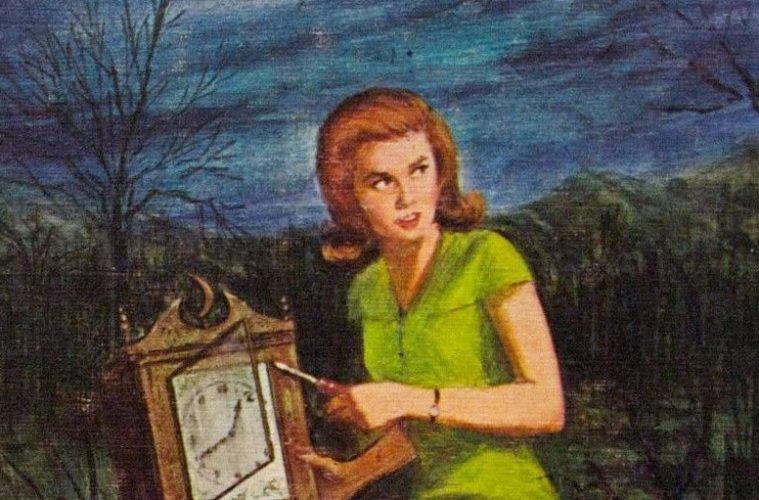

It’s this version of Nancy that you may have grown up with, the edited one who stars in 56 hardcover adventures. Those iconic yellow-spined books, published by Grosset and Dunlap in the 1960s and 70s, are what most people think of as official Nancy Drew canon. The series, called Nancy Drew Mystery Stories, has sold over 70 million copies since the first book, The Secret of the Old Clock, was published. Even the font used on those book covers is still everywhere.

But Nancy kept on evolving as her readers did. When Simon and Schuster acquired the rights to the character in the 1980s, Nancy modernized. Gone were the tasteful sheath dresses; covers of new books showed her driving speedboats and pining over boys. Since then, she’s gone to college, hung out in a Jacuzzi, dated men other than her faithful boyfriend, Ned, and been reinvented in graphic novel form. She’s been in two TV shows, the 1970s The Hardy Boys/Nancy Drew Mysteries and 1995’s Nancy Drew, in which she’s a criminology student in New York. And we have a new TV Nancy coming this year from the CW. If the trailer is anything to go by, it’ll be about as similar to the book series as Riverdale is to Archie comics.

Nancy has made it to film several times, too. In the late 1930s, Bonita Granville starred as a forgetful, somewhat ditzy version of Nancy in four B-movies, starting with Nancy Drew… Detective. Only two of the four were based on actual books in the series. And while the book version of Nancy stuck to relatively tame crimes like missing wills, stolen jewels, and haunted mansions, Granville’s Nancy investigates gruesome murders. This abrupt tonal shift undercuts the “plucky girl detective on an adventure” feeling that made the books so popular.

In 2007, millennial tweens got their own Nancy in the form of Emma Roberts, who plays her as a misfit teen with a passion for 1950s style that makes her a laughing stock to her label-obsessed peers. Though this movie is bang-on about some of Nancy’s most important traits—namely, her maddening competence in any situation, from escaping captors to defusing a bomb—it’s also just not very good. This is partly due to the inexplicable decision to relocate Nancy from River Heights to Los Angeles, sidelining familiar book characters like Ned, Bess, and George, and making Nancy herself seem like a bit of a dweeb. The movie isn’t based on any of the books in the series; the plot revolves around the decades-old murder of a Hollywood star, not the kind of case Nancy typically takes on. As her father, Carson Drew, Tate Donovan makes Nancy promise not to investigate crimes anymore, a fundamental misreading of a book character who often asks his teenage daughter to help him with his legal cases.

Most recently, It’s Sophia Lillis took on the role in 2019’s Nancy Drew and the Hidden Staircase, based on the second book in the Nancy Drew Mystery Stories series. In it, Nancy investigates an eccentric old woman’s haunted house and inadvertently uncovers a scheme to bring a new train route to sleepy River Heights. Though the plot feels classic Nancy and Lillis is a charming on-screen presence, the movie falls flat. Awkward attempts to update characters lead to things like Bess becoming a chemistry whiz and Ned morphing into a sheriff’s deputy. Nancy is more of a town nuisance than a teen detective who regularly shows up grown men, and the chemistry among the cast members never fully gels, possibly because so much of the dialogue is exposition.

The 2007 and 2019 movies both try to modernize Nancy, presumably to make her more relatable to today’s audiences. She uses a cell phone, discusses Instagram, skateboards around town, and goes to school, unlike book Nancy. She also has Black friends and acquaintances, a welcome change from the original series’ racism. But neither modernized version of Nancy feels much like the Nancy we grew up with. She first appeared on the literary scene five years after Jay Gatsby and was edited and reintroduced to readers one year after the young women in Rona Jaffe’s The Best of Everything. Thanks to these disparate cultural influences, she’s a strange hybrid of a 1930s teenager and a 1960s young woman. Nancy may be a rare character who is truly of her era(s) in a way that doesn’t translate to a contemporary setting. It’s like watching Hercule Poirot try to figure out Twitter.

If there is another common thread in these film takes on Nancy, it’s that she’s made into more of a, well, teenager: impetuous, exasperating, constantly getting into trouble. But that’s not the Nancy millions of readers know and love. The “real” Nancy may be eighteen on the page, but she exists somewhere outside adolescence. She foils jewel thieves the same way she dresses for a date: with an enviable, unflappable sense of self. She’s poised, confident, and capable, with a wardrobe full of clothing for every situation, along with an arsenal of skills (lock-picking, but also more obscure talents like skin diving and playing the bagpipes) that come in handy in the most unlikely circumstances. And though she’s chloroformed and tied up an improbable number of times over the course of the series, Nancy always manages to untie herself and get the bad guy to confess.

Nancy Drew is not a realistic representation of a teen detective, but that’s the secret to her appeal. Hardly anyone makes demands of her; her father is a benevolent barely-there presence, often absent for most of the book. Her sometimes-boyfriend, Ned, and best friends, Bess and George, follow her lead without question. Although Nancy uses her friends to solve crimes, you get the sense that she would be just as capable on her own. Even the police chief listens to her. It’s this authority and independence that mystery author Sara Paretsky has suggested is the reason behind Nancy’s widespread popularity. Nancy is a white feminist’s dream, a heroine who can go anywhere, do anything she wants (including breaking and entering) without repercussions, and, best of all, have men listen to her.

Maybe a character as competent and in control as book Nancy would be boring to watch on-screen. Aside from a streak of paternalism, Nancy doesn’t really have flaws, which makes her pretty insufferable. But whether she’s proving that a secret passageway is home to a group of smugglers or discovering a long-lost heiress trapped in a basement, it’s easy to forget about that insufferability and focus instead on the joy of a small blond teenager outwitting a bunch of men. That is what we really take from Nancy—joy in the knowledge that a teenage girl is right and that, for once, everyone around her knows it. We don’t want to watch her being chastised by her father or cautioned by the police. We want to watch her follow her instincts and ruin some criminal’s day because he underestimated what a girl detective like Nancy Drew can do.