When Alfonso Cuarón went onstage to accept his two Golden Globes—for Best Foreign Language Film and Best Director—for ROMA, I couldn’t help but think of the line that Sra. Sofia (Marina de Tavira) utters to Cleo (Yalitza Aparicio) as she stumbles through the door of her home.

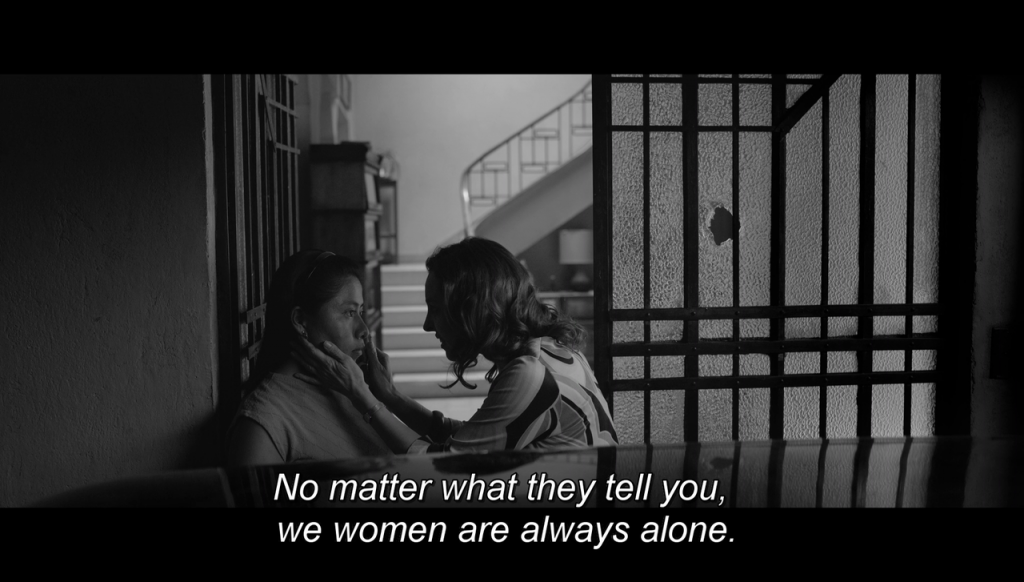

“No matter what they tell you, we women are always alone,” Sra. Sofia says after trying to park her car multiple times in the very narrow carport that is usually littered with dog poop. She seems to have returned high off revelation. Sofia has realized that not only is her marriage falling apart, but so is her life. And Cleo is there to witness. And Cleo witnesses everything.

Cuarón’s new film, ROMA, is a love letter to the woman who inspired Cleo’s character: Liboria “Libo” Rodriguez, his childhood caretaker. Taking place in 1970s Mexico City, Cuarón’s film zeroes in on Cleo, an Indigenous domestic worker who takes care of Sra. Sofia’s home and her four children.

After watching ROMA three times, I still felt like I was missing something. I still had questions. The first time, I found the film totally arresting. I wept as I watched Cleo lose a baby that she later admits she never wanted. I wept through the beach scene. But I also wept when I saw the single shot of Cleo in the bedroom with her boyfriend at the time, Fermín.

This was when I realized that I didn’t know anything about Cleo. All I knew was that she was with this boy, that she liked to make out with him at the movies, and that she was the caretaker of a white Mexican family. We don’t know what Cleo thinks about Fermín, we don’t know whether she loves him, we don’t know which village she left. Cuarón just brought us along for the ride. Then, I reminded myself of what Sra. Sofia said, and she was right. The women in this film are always alone, and while Cleo is just one woman existing on the plane of womanhood in ROMA, she seems to be the loneliest—and moreover, she is the character who is the least explored. We get to watch what happens to Cleo but not what she makes of any of it.

As I saw Cuarón go onstage to receive both of his awards, I couldn’t ignore the burning question I had: Why didn’t he bring Yalitza Aparicio onstage? I mean, Yalitza really was that special, wasn’t she? And I began to remember and retrace all the times when Cleo is alone in the film. Everyone around Cleo takes from her, but no one gives—and sometimes, the people around her don’t even know her name.

There is a saying that my mother tells me often in her choppy, Puerto Rican Spanish: “No te inclines demasiado o verán tu culo,” which means, “Don’t bend over too much or they’ll see your ass.” My mom says this to me out of fear that me or my sister will be taken advantage of emotionally; by friends, by men, by people in our day-to-day lives. It’s a protective phrase. And while Cleo is an Indigenous Mexican woman, I wonder whether her mother ever said anything along those lines to her. Cleo constantly bends over for this family, and while it at first seems to be out of genuine love, it soon starts to feel like it is because she is trapped—trapped by her class, her race, her gender, and her body.

In an interview with Variety, Cuarón discussed some of the thought process behind his now Oscar-nominated masterpiece. In the interview, he seems to be aware of the fact that there were race, class, and gender dynamics involved in the living, and later retelling, of his and Libo’s story. He says that he knows that Libo was a real person with a whole life of her own, but I’m not sure that this idea landed on its feet. It makes me wonder whether the way Cuarón imagined Libo’s story was really an idea, a romanticization, or even just a longing for what once was. Cuarón’s attempt to tell Libo’s story was in no way unjustified—if anyone was going to tell it, it was him—but I wish I knew more about her. I didn’t want to just watch Cleo suffer.

As the film trudges on, Cleo gradually begins to morph into a symbol of loss, and this metamorphosis explodes into something so massive that I just couldn’t take it. I wept for the entirety of the final act. First, she leaves her village to work for this family. Then, she loses Fermín after he finds out that she’s pregnant. Then, she loses the child during childbirth—a particularly heart-wrenching scene for me, but a brilliant one nonetheless. Then, she almost loses two children, Pepe and Sofi, to the unruly current at the beach—and although she saves them, she wasn’t even supposed to be working. Cleo was supposed to be on vacation with the family and recuperating after the toll that losing the baby took on her.

But before all of these terrible losses and traumatic events happen to Cleo, there is a brief exchange in La Casa Del Pavo, a restaurant where Cleo, Adela, Ramón, and Fermín meet up before they leave to go to the movies. As Cleo and Adela get up to leave, Fermín stays behind for just a few seconds to take a sip of Cleo’s leftover soda. At first, this sip was endearing, but as terrible things kept happening to Cleo, I found myself trying to pinpoint where the turn of events started, and it seemed to be with that sip of soda. This is when I knew that there was a violent coarseness to Fermín, and that thiscoarseness would mar Cleo’s story sooner or later. It’s after that sip that it begins to take a downturn.

I felt grief for Cleo’s soda at that moment because I knew that Fermín was never going to take care of her. After the grief I felt for her soda, I felt the same grief for the cup that falls to the ground, the one thatbreaks at the New Year’s Eve party she goes to.

Mexico at the time was in a state of reaction and upheaval. There were many protests and state-sponsored acts of violence against revolutionaries, particularly students. The day that Cleo goes to buy her crib with Teresa, the grandmother of Sra. Sofia’s children, a protest gets out of control. There is police clubbing, screaming, and gunshots. Los Halcones (The Hawks), a paramilitary group trained by the United States, were also part of the student repression and state violence. These young men run up to where Cleo is buying her crib, and it’s here that we finally zero in on her.

It felt like everything that I was watching stopped for a moment. It was just Cleo face-to-face with a gun. And it is here that I realize: Again, Cleo is by herself. Though Teresa puts her arm out to protect her, there is nothing that she could have done for Cleo. Cleo and her baby are on their own. Cleo is always on her own. I wonder what Cleo would have thought about the political turmoil that Mexico faced at the time. All we learn is that Cleo didn’t want her baby. All we learn is that Cleo gives endlessly. All we know is that no matter how much she gives, Cleo will feel guilty forever.

Since ROMA’s release, Yalitza Aparicio has become a star—she’s been on the cover of Vogue Mexico, she’s been to award shows, she’s done countless interviews. She’s given a lot of herself to help tell this story. I wish Cuarón would have held her hand onstage. It took him until his second award of the night to thank her.