Googie visuals, De Stijl palettes, art deco facades, Miesian skyscrapers, and Corbusian furniture. These are just some of the wonderful architectural features that make up the world of Brad Bird’s The Incredibles (2004). My seven-year-old self was mesmerized by this animated terrain of design. Even then, I registered the beauty of its sleek, modern renderings. Fast-forward fourteen years, and Brad Bird has finally given us the sequel we’ve all been waiting for. Incredibles 2 is faithful to the signature mid-century modern aesthetic of its precursor, indulging us in more beautiful, historically-accurate architectural surroundings, which I will try and unpack for you.

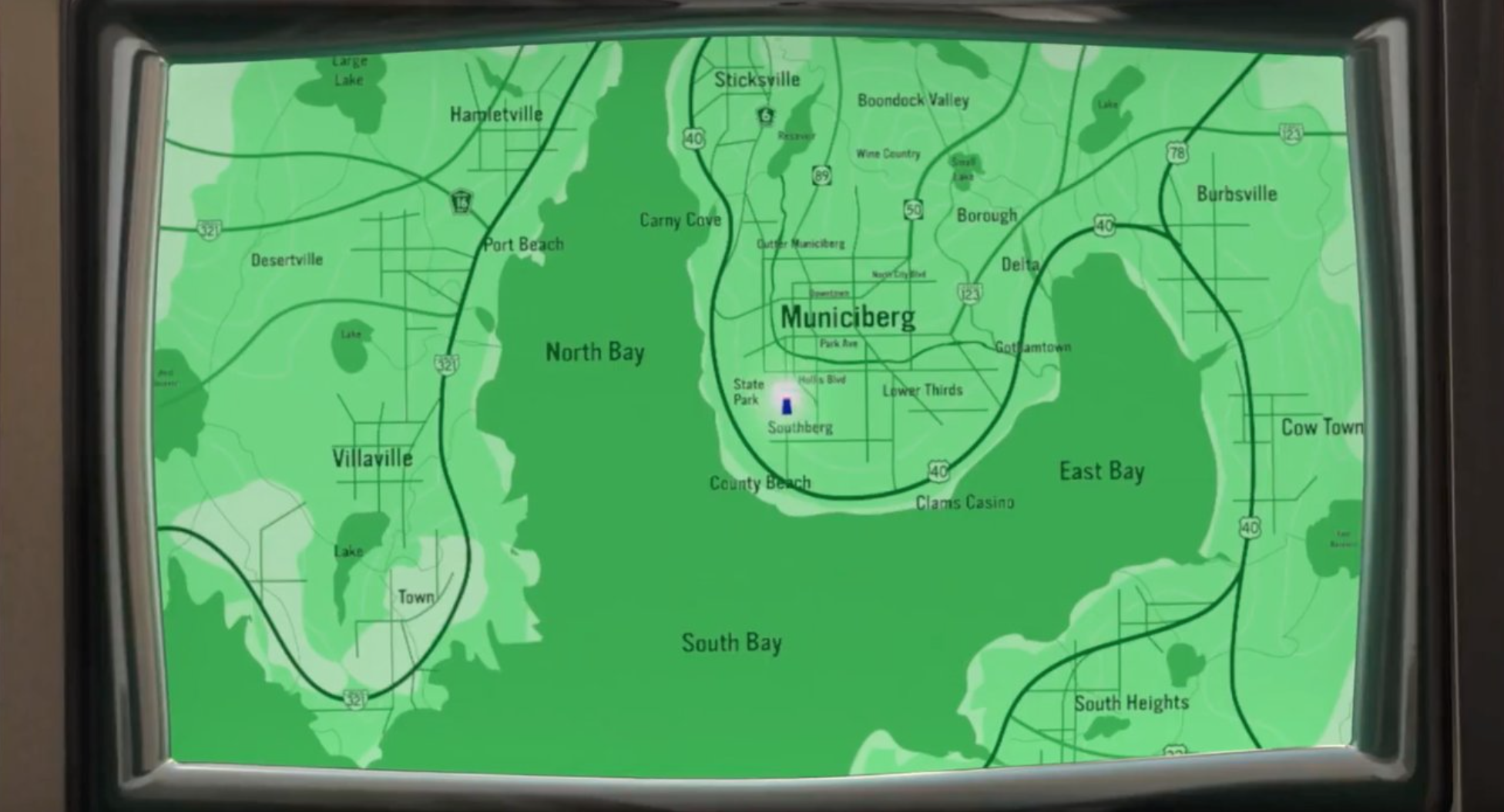

Incredibles 2 picks up where we left off, with the Parrs fending off the Underminer. We’re back in Municiberg, an archetypal post-war North American city with a densely-packed commercial core. Downtown Metroville offers us Louis Sullivan-type office buildings, featuring grand ground-floor entryways, followed by identical vertically-stacked tiers that are capped with a distinct form at the top. The opening of The Incredibles is actually set in 1947, giving us a better view of the warm, terracotta-clad, Sullivanesque buildings (think Wainwright), along with some beautiful art deco facades. The film skips ahead fifteen years, putting us in 1962. Modern steel and glass skyscrapers dominate the cityscape, taking over their bricky precedents. Incredibles 2 gives us that same monochromatic Miesian cityscape.

Photo: Disney Wiki

As Elastigirl (née Helen Truax) stretches and swings past buildings, we get a panning shot of Municiberg. The high-density monoliths are organized in a rectilinear and orthogonal grid, very much in keeping with Le Corbusier’s utopian plan, Radiant City (Ville Radieuse). Le Corbusier would probably delight in the fact that many of Municiberg’s buildings are also lifted by pilotis. While Municiberg’s downtown plan is gridded, its complete master plan can be thought of as a series of concentric rings – the center being a high-density commercial core, followed by an industrial buffer zone, and finally a low-density residential suburb at the peripheries.

Photo: Twitter

With the advent of industrial capitalism and post-war population growth, cities began to exponentially grow, limiting space and resources, and pushing denizens to greater surrounding areas. Zoning laws had divided up cities, and highway acts allowed for accessible commutes to downtown, making suburbs a logical solution. The Parr family’s home in the first movie is a prime example of a post-war suburban American home. A wide shot of their neighbourhood shows us just how Levittown-esque their suburb really is.

Photo: Mister Comfypants

If you recall, Mr. Incredible (né Bob Parr) holds a boring 9-5 office job in The Incredibles. His job is, of course, located in the downtown core, which he commutes to in his dull automobile (a sure nod to post-war American automobile culture).

Photo: Pixar Planet

The imposing repetitive layout of Bob’s office is a direct reflection of one of Sullivan’s Tall Office Building laws: “[a]n office being similar to a cell in a honeycomb, merely a compartment, nothing more.” What was meant to be universal and democratic was instead highly prescriptive and aesthetically homogenizing. One of the inherent problems with modern architecture principles was that they ignored human diversity and contradictions, making one universal design that everyone was supposed to adhere to. (This also applies to housing typologies re: Levittown homes.) The restrictive design principles of modern office buildings are pointed out to us by Bob’s exasperation as he is literally boxed in his office cubicle. We actually get a comprehensive wide shot of the office floor: a grey, tediously banal design of identical cubicles arranged in a Cartesian grid. Yikes.

Photo: Pinterest

In the essay, “The Chicago Frame,” Colin Rowe argues that the steel frame became a catalyst for modern architecture. The advent of the elevator and possibility of skyscrapers resulted in the demand for the rational, economic construction of business offices. The steel frame was the most efficient construction method for skyscrapers – a means to an end that eventually became a symbol of wealth and burgeoning American capitalism. It makes complete sense why North American office buildings are the way they are. And it makes sense why we read and understand Bob’s very relatable frustration. Thankfully, he leaves that job to pursue his destiny as a Super.

Notice Municiberg’s buildings bear a strong resemblance to modern skyscrapers, namely those by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. | Photo: YouTube

In The Incredibles, as in life, conservative suburban houses and modern metropolitan office buildings are subtly paired together. These two very different building types came to represent the heteronormative nuclear family. Using this model, architecture represented men as producers, working in their rational modern office buildings, and women as consumers, sheltered in their suburban domestic sphere. Elastigirl’s role in the sequel breaks this structure as she lands a job to make Supers legal while Bob takes care of the kids.

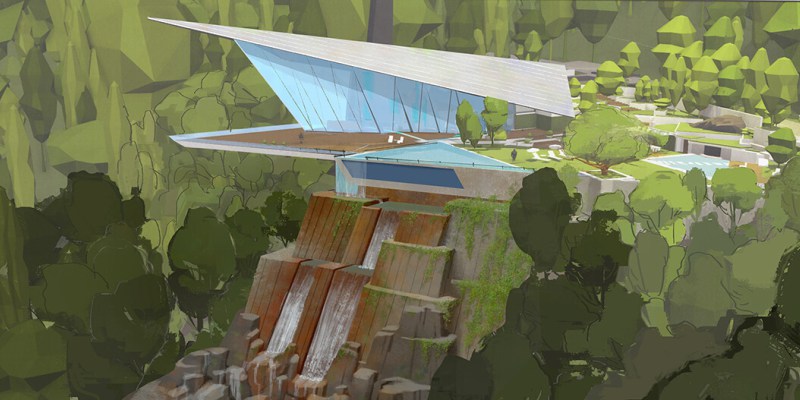

I will now shift to Municiberg’s residential typologies. The architectural protagonist of the sequel is probably Winston Deavor’s multibillion-dollar home – one of several – which he lends to the Parrs. Nested on the edge of a secluded green hillside, the house is cantilevered in a typically Googian fashion, its roof projecting at an upwards-sloping angle that is both structurally sophisticated and cartoonish (bougie Googie?).

Photo: Inside the Magic

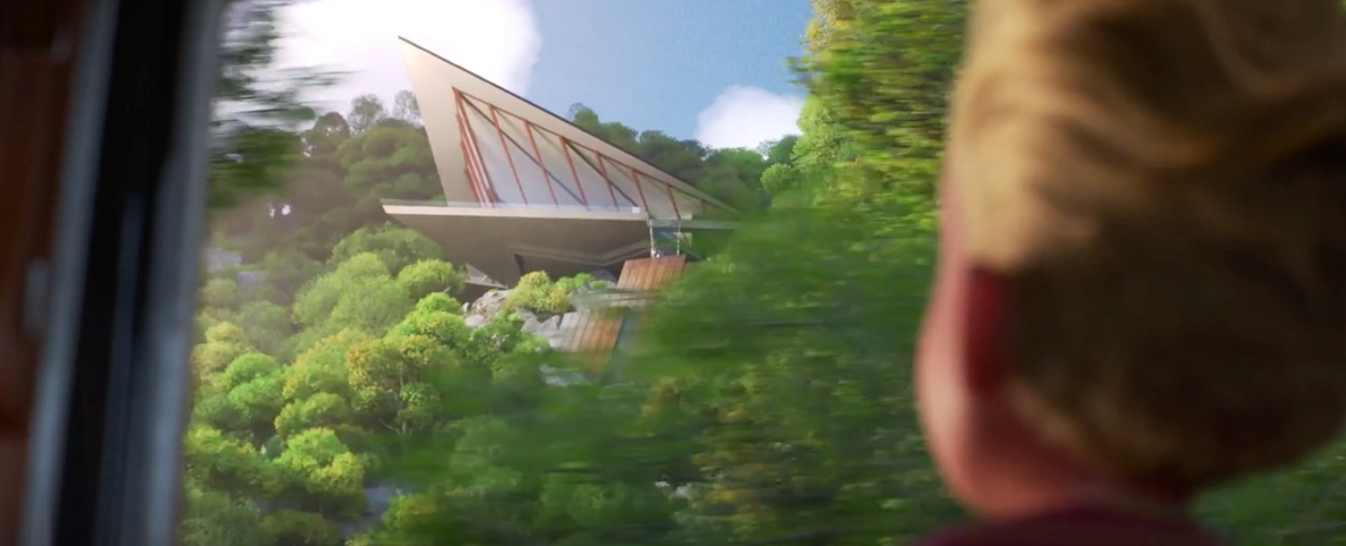

“Deavor bought it from an executive billionare who liked to come and go without being seen,” Bob informs us. Ironically, one of the key features of this house is its sprawling glass curtain walls. While the house’s transparency and client’s desire for privacy are contradictory, we come to learn that there are several hidden exits. The important thing about this house is that it contains those hidden exits; they are a point of reconciliation for both architect and client – something that Mies was unable to achieve in his design of Edith Farnsworth’s weekend house. Nevertheless, its transparency is complex, operating on both a literal and phenomenal level. (See Colin Rowe and Robert Slutzky’s essay on transparency.) The glass curtain walls are literally transparent, while the abstracted spatial organization of the house demonstrates a kind of phenomenal transparency. As the Parrs are driving to the house, we get a glimpse of its exaggerated angular shape.

Photo: Medium

The house’s slanted glass walls give us an impression of its interior volume. The acutely angled slant also reduces the interior space, eventually converging at the edge of the cliff where the planes meet. Despite the house’s large transparent windows and open plan, its deeper spaces are hard to read. In the films, architecture and technological progress are inseparable. With Deavor’s house, technology is embedded through hi-tech controls, including sliding floors, doors, and sophisticated water features. The technological feats of Deavor’s house also help create layers of privacy. The extravagant ceiling-to-floor waterfall, for example, partitions the living room space from the entry hall and upstairs bedrooms, creating a layer of opaqueness that cleverly blurs interior legibility.

Photo: Pixar Planet

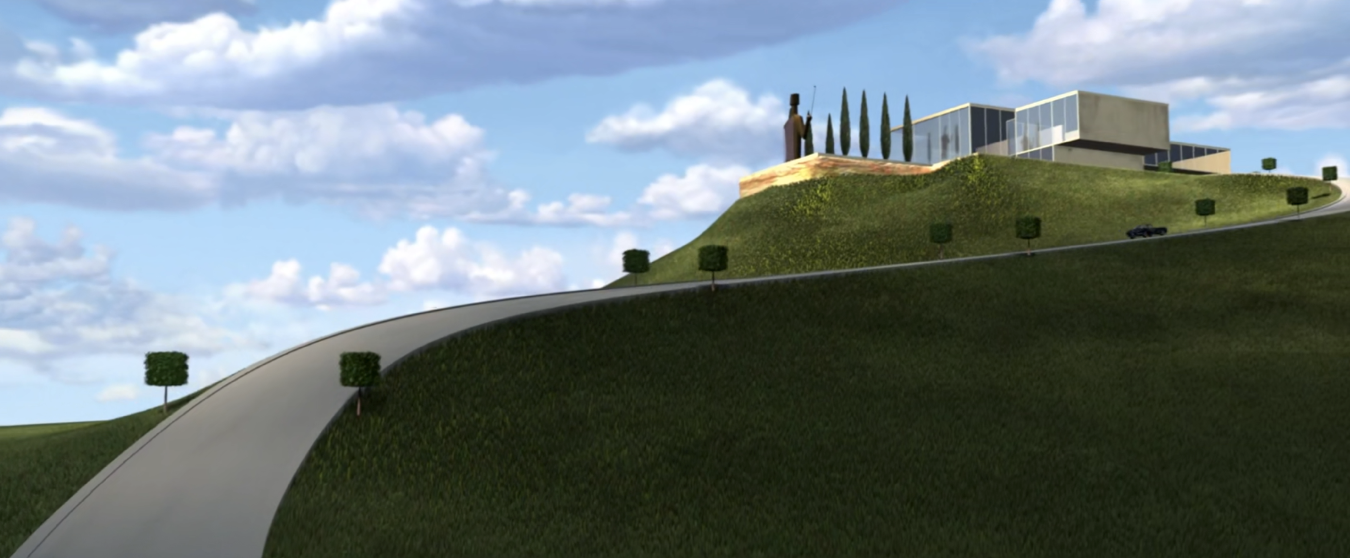

Despite the innumerable impressive architectural feats of The Incredibles, Edna Mode’s house will always be my personal favourite. Perched on top of a remote green hill, the house is made up of stacked boxes with glass and concrete faces. Regardless of where you lie on the architecture enthusiast spectrum, you already know it’s “high design.”

Photo: Pinterest

“It’s avant-garde, dahling.” | Photo: Best Ever Albums

The house is formally pure, demonstrating the richness of simple vertical and horizontal construction. The bright red planar door is a beautiful example of De Stijl, giving us a hint of the De Stijl accents to come.

Gerrit Rietveld’s Schröder House is a pivotal example of De Stijl architecture and furniture design. The house’s defining features are its sliding doors, linear planes, and primary colours – essentially an explosion of a Mondrian painting. | Photo: Dwell

Terracotta pitchers (evocative of ancient Greece) sit encased behind glass compartments on either side of the narrow entry hall. After the corridor, we are met with an enormous space, complete with a colossal Greco-Roman bas-relief. (I love her tacit affinity for ancient art.) Marble steps, encircling the space, take us down to an open atrium, carved into the house’s ground level.

Photo: Pinterest

Despite the house’s monumental scale, it contains astonishingly little. Nevertheless, nothing is random. It is clear that each object was carefully selected and curated to make the space what it is – an architectural mash-up of Edna Mode Fashion. Her sofas, faithful to De Stijl in their red upholstery, are very similar to Le Corbusier’s iconic LC3 sofas, complementing her avant-garde persona and the high modern aesthetic of her house.

The LC3 Sofa by Le Corbusier | Photo: AptDeco

Despite existing in the fictional, animated world of superheroes, The Incredibles has always felt believable. This is largely because of the film’s historically accurate architecture – carefully selected and sustained through the incorporation of canonical mid-century modern features that are, if not immediately discernible, familiar to us on some level. Aside from its somewhat predictable plot – don’t even get me started on the Screen Slaver and his clichéd Debordian critique of modern society – the sequel gives us a beautiful, comprehensive display of modern architecture, one that symbolizes technological progress, optimism, and prosperity.