Sometimes you watch a film and it stays with you. Fragments and feelings drift in and out of your mind, unexpectedly catching you off guard. I first saw Cate Shortland’s Somersault (2004) during a time of transition in my life. A low-budget but atmospheric Australian coming-of-age film, it felt different from other films of its type. Rather than the traditional coming-of-age tale of distant reflection and lessons learned, it had an immediacy to it. It became etched in my memory, scenes or images sometimes coming back like echoes of who I was back then.

Somersault tells the story of impetuous 16-year-old Heidi (Abbie Cornish), who leaves her home in suburban Canberra after kissing her mum’s new boyfriend. She heads for the mountain resort town of Jindabyne. There, she meets local farmer’s son Joe (Sam Worthington), and they form a relationship of sorts.

The film explores themes often tackled by the coming-of-age genre. A feeling of vulnerability, of not quite knowing who you are yet, with the lead character embarking on a journey of discovery. Often, these stories are autobiographical and told in flashback, with the main protagonist recalling their own youthful journey of discovery years later, having learned their lessons and moved on.

John Duigan’s The Year My Voice Broke (1987) tells the story of Danny (Noah Taylor), a socially-awkward 1960s adolescent who falls in love with his best friend, Freya (Loene Carmen). Duigan based the film on his experience growing up in a small country town in Australia. The first part of what was hoped to be a trilogy, the film was succeeded by 1991’s Flirting, which follows Danny to an all-male boarding school where he falls in love with Thandiwe (Thandie Newton), a Ugandan-Kenyan-British girl from a nearby school. The film touches on racial politics and social convention, as well as the usual sexual and romantic discovery of the genre. No third instalment of Danny’s story has been made by Duigan as of yet.

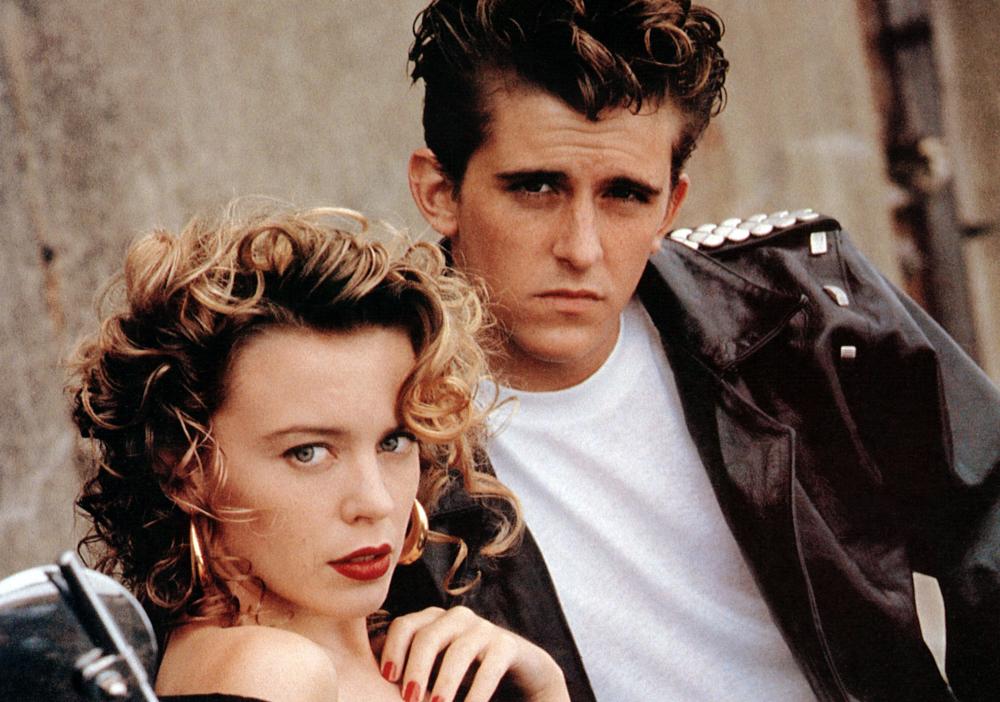

Discovery, disobedience, and love—not to mention a romanticized version of past decades—also feature in popular Australian film The Delinquents (1989), which starred Kylie Minogue and Charlie Schlatter as 1950s small-town teens Lola and Brownie. The two fall in love, but, because of their age, must fight their parents and the authorities to be together.

Shortland’s Somersault, although containing similar themes, has a more British aesthetic. There are parallels with David Leland’s Wish You Were Here (1987), a poignant, delicately observed coming-of-age drama based on the early life of Cynthia Payne. The film tells the story of 16-year-old Linda (Emily Lloyd), who feels bored and frustrated by her life in a small British seaside town in the 1950s.

Heidi’s character in Somersault is very similar to Linda. They both crave love and affection, but seek solace in sexual relationships at a young age. The contrast between this burgeoning sexuality and the end of childhood is a key theme in both films. Heidi takes her journal with her when she runs away, and it’s full of pictures of glittery unicorns and childish musings. In Wish You Were Here, Linda rides her bicycle around town, a toy windmill attached at the front spinning with the breeze as she moves. Both act with youthful spontaneity throughout.

In Somersault, Heidi travels away from home to find herself. Often, it’s easier to run away from your problems than stay and have that difficult conversation. She can hide in a tourist town; it’s transitory and anonymous. But she’s there out of season, and so she stands out. Like Linda in Wish You Were Here, Heidi receives inappropriate sexual attention from older men, who then blame her for inviting it, threatening that their daughters should stay away from “girls like you.”

Similar themes of sexuality in adolescence and inappropriate relationships are also explored in other British coming-of-age films of the 2000s, including Andrea Arnold’s Fish Tank (2009) and Paweł Pawlikowski’s My Summer of Love (2004).

Often, it feels as though Heidi is playing at being a grown up. She talks in clichés, speaking with someone else’s voice because she doesn’t yet have the words. When she finds a job at the local petrol station, she takes pride in having her own nametag, as if it symbolises a step towards adulthood. Yet, when told that she can have something to eat during her shift, she chooses a doughnut.

Somersault is a beautiful film and a sensory experience. This is a remote part of Australia not often seen on-screen; the snow is in stark contrast to our usual impression of eternal sunshine and seems alien somehow. It uses a colour palette to match the landscape of the mountains and lakes, all cold blues and washed-out greys. Heidi’s delicate features are shown against the wintry landscape, exploring near the water at the foot of the mountains, her red gloves standing out playfully against the snow. She looks small and fragile against the wide-open vistas. Heidi returning to the calmness of the water’s edge is a recurring motif throughout.

But when she enters the resort bar at night-time, the screen fills with soft reds and oranges, a feeling of warmth and comfort that echoes her need for human contact and beckons us in with promises of precious solace.

The film also uses changes in pace, a slowing down of time to match the altered state of Heidi’s feelings as she explores her surroundings. The soundtrack, too, ebbs and flows with her mood. Heidi constantly uses her hands to express herself, both in her tactile exploration and discovery of the world around her, and in her relationship with Joe.

Somersault also captures Joe’s emotional journey. He is greatly affected by Heidi’s arrival, but we feel that he is already struggling with his own identity, and Heidi is merely a catalyst. A few years older than her, Joe is still playing at being an adult, too. He responds to Heidi physically, through touch and sexual contact, but when she reaches out emotionally, he shuts her out. He can’t even bring himself to hold her hand in public. Her presence in his life challenges his emotions, but he can’t express his feelings, his inner frustrations palpable in every scene.

Joe inhabits a close-knit rural community in Jindabyne, beyond the transitory tourists. The young characters plot their imaginary escapes but are tied to the town by family and duty. Joe’s relationship with his dad is strained and uncommunicative. His conversations with enigmatic neighbour Richard (Erik Thompson), returned to sort out his dad’s farm after his death, suggest a longing for a new life. Richard is gay, and this adds to Joe’s journey of discovery and change as he explores his feelings for him. Heidi also threatens his lifelong friendship with Stuart (Nathaniel Dean).

The film captures the awkwardness of young love and sexual discovery beautifully. Heidi and Joe experience a silent intimacy, with exploration by touch and without words. They both seem scared by their own feelings. “Do you love me? Am I your girlfriend?” pushes Heidi when they finally venture out for a meal. His lack of overt feeling results in her eating raw chillies for attention. A petulant, childish reaction to an adult situation that neither of them can yet handle. Joe tentatively admits his feelings for Heidi when talking to Richard: “When you leave, you still feel her on your skin.”

The film culminates in Heidi taking an extreme risk. She gets drunk in the bar and is taken home by two young men who sense an opportunity for a good time. She lacks self-control, but also a sense of self-worth. When Joe discovers her and throws the two men out, a naked and vulnerable Heidi simply says, “I didn’t want to be by myself.”

Heidi’s lack of understanding of the impact of her actions means that she hurts those that are kind to her. She lashes out cruelly at her caring landlady, Irene (Lynette Curran), but Irene still gives her solace in her time of need. When Heidi admits her wrongdoing, Irene persuades her to do the right thing and call her mum. “Whatever you’ve done, your mum will always want to see you,” she reassures her. You feel a weight lift from Heidi.

As Heidi gets ready to leave town, Joe finally reaches out to her, but she doesn’t take his hand. It’s over, and they have both moved on emotionally.

Inevitably, Heidi returns home. We don’t hear the conversation with her mum on the phone, we don’t see them reunited, but we feel it and see it in her face as she leaves. In Somersault, we are not listening to the narration of an older, wiser version of the person looking back. We are in the moment, exploring and discovering alongside Heidi. Things have changed under the surface of the water, and we feel the ripples with her.