“Tell me something, Ma. What did Papa think—deep in his heart? He was being strong—strong for his family. But by being strong for his family, could he lose it?” — Michael Corleone, The Godfather Part II

Before the gunshots, it had been a long day of celebration; Anthony Corleone had been confirmed in the Catholic church. Family flew in from New York City. There was dancing and a band—one that didn’t know any of the old Sicilian songs, though (something to be lamented). In Michael Corleone’s (Al Pacino) uprooting of the family from New York to Lake Tahoe, something important had been lost. Their connection to their Sicilian heritage was slowly fading. Whether or not he was aware of it yet was a different story entirely.

While the festivities from earlier in the day had technically been in honor of Anthony, like many parties that happen when you are a child, the party just happened around him and not exactly for him. But because he is a Corleone, that means that the party was never really his to begin with, only a façade for Don Michael Corleone to conduct business safely. Any celebration held by the Corleones is marked by an intertwining of business deals and sacred oaths sworn in the presence of family. This is not lost on Anthony, however, which we see as Michael tucks Anthony into bed after the gunmen have been found (and killed) on the property.

“Did you like your party?” Michael asks.

“I got a lot of presents,” Anthony responds.

“I know. Did you like them?”

“I don’t know the people who gave them to me.”

“They were friends.”

The Godfather trilogy is inherently a commentary on family: the ways in which the organization of the mafia can mimic familial structure, a questioning of what one is willing to sacrifice for blood relatives, a negotiation of familial loyalty and business savvy. To further study the connection between the bonds you are born with and the bonds you create, The Godfather Part II juxtaposes Michael Corleone and his father Vito’s approaches to being husbands and fathers, examining their motivations and responsibilities, and highlighting the places where they intersect and deviate to warn about the danger inherent in conflating family and business.

The Godfather Part II follows two distinct, adversely proportional plot lines: the creation of the Corleone mafia family by Vito Corleone (Robert De Niro) – a Sicilian immigrant – at the turn of the century, and the decline of the Corleone’s influence under Michael as he struggles with personal crisis. The interplay of the two narratives are a call and response through time. As Michael’s ability to keep his family together wanes, Vito navigates his newfound influence as a way to protect his young family and community. Both men are presented as shrewd businessmen, but it is their difference in raising their families that ultimately separates them, indicting Michael and acquitting Vito.

At the turn of the century, Vito escapes from his native Sicily after the murder of his family by the local Don. He comes of age in America, living in an Italian immigrant neighborhood in New York City. When we first see Vito as a grown man, he is in a small apartment, gazing lovingly upon his infant son, Santino. It’s shot with a delicacy that almost feels out of place for a mafia movie, even one so focused on the familial. Establishing Vito as a family man from his introduction conveys his emotional priorities to the viewer. Vito is not presented as a man hardened by violence he has faced and the cruelties inherent to being an immigrant, though the character could have believably been played that way. Instead, he gracefully refuses handouts when he loses his job, a sign of respect for his friend and employer. He brings home a pear as an unexpected gift for his wife and kisses her tenderly over dinner. When he watches an Italian play with his friend Genco, he remarks that while the actress onstage (the object of Genco’s admiration) is beautiful, for him “there is only [his] wife and son.” The foundational conceit that Vito’s character is built on is that he is a man who is in love with his family and his adopted community—that the darkness doesn’t feel as dark when you’re holding your children.

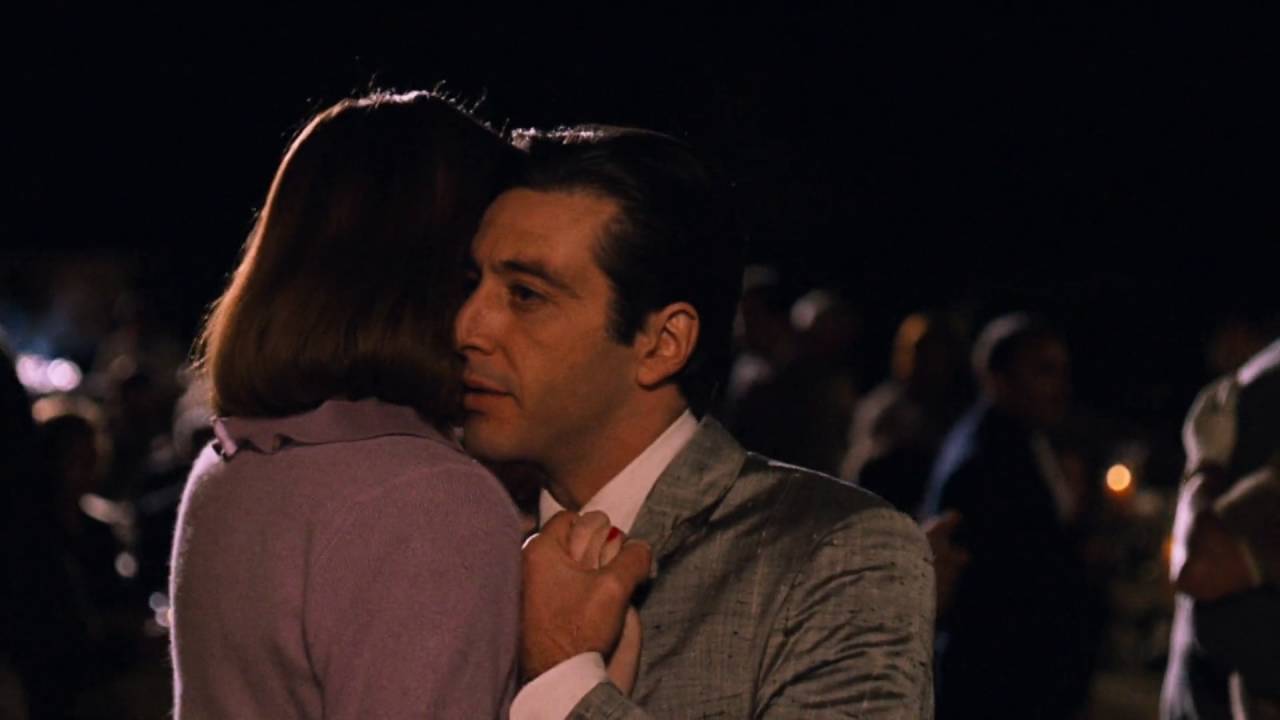

When we see Michael for the first time, we see him at his son’s confirmation and the party that follows. While he seems removed from the events unfolding around him, he is completely in control. He remains composed as a state senator accuses him (rightly so) of trying to transfer his underworld influence into political leverage. With a nod, he summons his bodyguards to carry his brother’s drunk wife away from the dance floor. He dances with his wife Kay (Diane Keaton), who is concerned that he isn’t severing ties with the family’s more nefarious connections as quickly as he promised. He assures her that the Corleone family’s legitimacy is forthcoming. But we know better.

The intercutting of Vito’s narrative serves to undercut Michael’s narrative. As Vito gains friends in the community, Michael only finds enemies. We believe that Michael is doing his best to expand the Corleone family’s domestic and international presence, only to watch the empire start to shake from unintentional betrayal at the hands of his older brother, Fredo (John Cazale). With his father and mentor gone, we see Michael start to falter under the weight of his responsibility to the business, leading to emotional distance between him and his family.

Photo: YouTube

In the midst of this professional distress, Michael receives word that his wife Kay has had a miscarriage. He is distraught, but there is no adequate time to grieve, no time to return home to comfort Kay and his children. Instead, he continues to work. When he does come home, he finds Kay in the midst of domestic duties and does not make his presence known. It’s a profound isolation, given the warmth and security of Vito’s narrative.

Instead of bringing his concerns to his family and addressing the distance head-on, Michael asks his mother about how his father handled the pressures of being both a Don and a father. “He was being strong—strong for his family. But by being strong for his family, could he lose it?” he asks. His mother assures Michael that he could never truly lose his family. But we know better; loss plagues the Corleones.

For Vito, his ever-growing family is his connection to something he had lost in Sicily, and it becomes a way to cohesively bridge the gaps between his life here and his past there. Vito’s need to keep his family safe stems from the injustices perpetrated by those people like Don Fanucci who claim to “protect” a group of at-risk people, such as the Italian immigrants that populate his New York neighborhood. Don Fanucci is a painful reminder of the man who took everything from him in Sicily, Don Ciccio. Fanucci runs a protection racket, demanding cuts from each business in the neighborhood and offering his “protection” in exchange. Vito is haunted by two powerful Dons who threaten not only his livelihood but also the livelihoods of his family and friends. His family can never be safe under the facsimile of the ancien regime of Dons who take from those they promise to look after. Vito kills Don Fanucci. But it doesn’t feel like an act of malice. This is an act of liberation and protection.

In another filmmaker’s hands, perhaps the scene would have cut after Fannuci’s murder, depicting Vito’s change from a passive to an active participant in his life. But that’s not where the film cuts to intermission. Instead, we see Vito reverse his route, ending up at his stoop, where his wife watches their children—three sons that will eventually grow up and vie for his approval. He plucks baby Michael from her arms, cradling him against his chest, and gently whispering in Sicilian, “Michael, your father loves you very much.”

The last time we see Vito in The Godfather Part II is when he brings his family to his native Sicily. He is there to kill the Don that forced him to flee his homeland. But he is also there to connect his family to their collective past. As they leave, he holds Michael and helps his youngest son wave goodbye to the people on the platform. It’s tender and sweet, and it’s a memory that Michael shares with his dead father. It serves as a reminder for the morose Michael that his family is the most important, most precious thing he has—and he is losing them.

Instead of being figuratively cut off from Michael, Kay is physically separated from her family after Michael discovers that her miscarriage was an abortion; she decides that bringing another one of Michael’s children into the world is in itself a cruelty. The child’s father is a gangster, and even more importantly, he is a man that did not uphold his promise to bring the family business into the legitimate world. Michael takes custody of their children. He closes the door on her yet again, mimicking the end of the first film.

Michael, who cannot see past his brother’s betrayal, orders a hit on him. Fredo is shot mid-recitation of a Hail Mary prayer. Silence falls across Lake Tahoe, marking the end of an era—the days of Vito Corleone are long gone. In killing his brother, Michael has made his choice; business will always precede familial loyalty. In the final moments of the film, Michael sits outside in deep contemplation as the autumn leaves pick up and drift away. He is alone.

Vito and Michael are the perfect foils for one another. While Michael loves his family, his love is tempered with his need for control. His family is a physical reminder of what’s at stake in the darkness. He controls Kay and his children’s movements, sometimes from thousands of miles away, feeling that this will keep them safe, unaware that it drives them away from him. It speaks to how he sees them: something close to props, reduced to extensions of himself. Vito’s way of parenting and expressing his love for his family is to bring them into the inner chambers of his life. He centers his life around them, considering how his decisions affect his children. They are first and foremost. While Michael also concerns himself with how his actions will affect Kay, Anthony, and Mary, he actively creates distance. In this, the two fathers of The Godfather Part II deviate.