Rob Sheffield, a music journalist for Rolling Stone, recently ranked each of Taylor Swift’s songs in the subjective order of worst to best. He placed 1989’s “Bad Blood” dead last, calling it “[m]elodically parched, lyrically unfinished, rhythmically clunky.” “Bad Blood”—a song about the fallout between Swift (if we are to believe that Swift is an autobiographical songwriter and thus the subject of this song, and I do) and a close friend (ostensibly Katy Perry) that reached near ubiquity on the radio in 2014—is all of the things Sheffield accuses it of being. Embarrassing in its pettiness, obsessed with betrayal, almost ugly in its childish emotions. Articulating betrayal-caused heartbreak in a platonic relationship always comes off as childish, even though time touches and molds friendship the way it does any other relationship.

In “Bad Blood,” Swift knows that she sounds childish, but she’s making us consider how friendship can be fraught in the same ways as romantic or familial relationships, that the pain can cut just as deep—that “time can heal / but this won’t,” and that there seems to be no middle ground for this kind of grief.

Sometimes, time can heal friendships by putting temporal distance between the inciting incident and the people involved. But sometimes, time cannot heal; rather, it can harm. Some relationships, like the one explored in Elaine May’s Mikey and Nicky, are hindered by their length and history. May investigates the malleable nature of time in the lifelong friendship between two low-level Philadelphian gangsters, Mikey (Peter Falk) and Nicky1 (John Cassavetes, at his most devastatingly handsome), by making time a dual-purpose thematic device—a bridge and a weapon, which she uses to explore their shared history of their fraught friendship and their mutual betrayal.

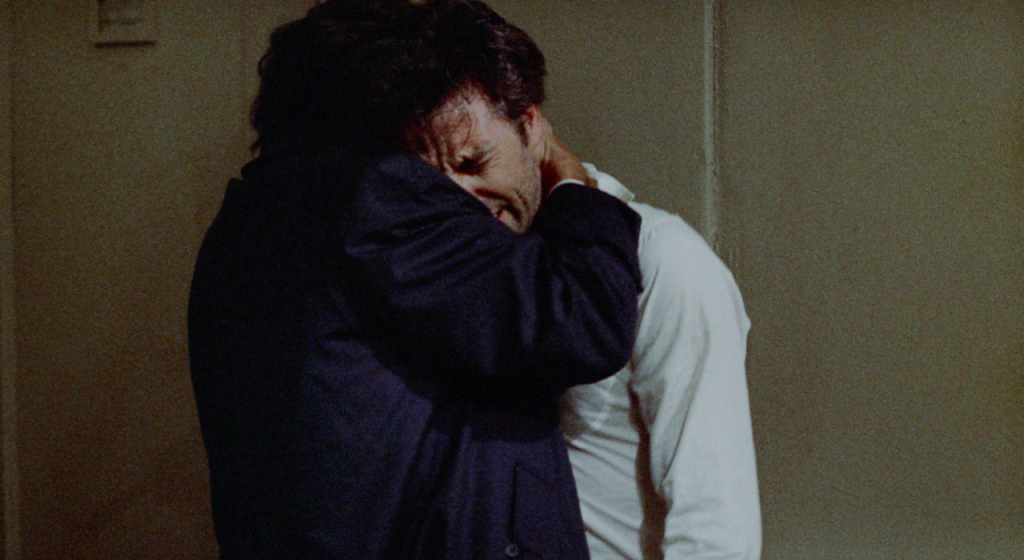

The film begins with Nicky’s plea for Mikey’s help. He believes that he’s in trouble with their boss after reading that one of their small-time colleagues was found dead. Mikey dutifully arrives to help his friend out of this scrape; he’s practiced in the art of bolstering Nicky through his emotional breakdowns, which are implied to be somewhat frequent. When Nicky—strung out, paranoid, and embarrassed—refuses to let Mikey into his hotel room and shouts through the door, “I don’t want you to see me like this,” Mikey responds, “What way am I going to see you that I haven’t seen you before?” Their shared history of Mikey seeing Nicky at his absolute worst brings Nicky comfort, and he melts, weeping, into his friends arms, who holds him with no reservations. It may be the most tender scene between two men who are not lovers in the uber-masculine gangster films of the mid-70s. He force-feeds Nicky an antacid, (“When you say ‘I’m in trouble,’ I come and I bring Gelusil”), runs to the coffee shop on the corner to get a full cup of cream (as a lactose intolerant person, I remain unclear on how this is supposed to help Nicky), then offers to help him get out of town, all while assuring him that no one is after him. They switch clothes to throw off anyone who may be following them, and Mikey hands his father’s watch over to Nicky.

Mikey’s watch is the most obvious symbol of time, but May uses it so well in the film. Because it’s an heirloom of particular importance to Mikey (one of the few objects he has from his deceased father), the watch takes on additional significance. By giving Nicky the watch, Mikey is putting trust in their friendship. We’ve seen Nicky at his most feckless, most vulnerable moment. This is Mikey’s moment of vulnerability and openness.

May begins the film with tenderness and vulnerability to underline the friends’ (particularly Nicky’s) ability to be cruel to one another. However, there’s a sense of distance between the two that becomes apparent as they wander through the night. As they stumble through Philadelphia, they fall through time, recounting moments from their past to both emphasize their bond and foreshadow that their bond is not as strong as it once was.

We realize early on that not only are their bosses after Nicky, Mikey is instrumental in leading the hired hitman to Nicky. After reassuring Nicky in the hotel that he’s paranoid for no reason, this realization is acidic and heavy. Mikey gives himself away without realizing; he keeps nervously checking the clock on the wall, asking if the phone just rang. Nicky watches his suddenly-anxious friend watching the clock, and his face falls. It’s a sudden realization: Mikey has betrayed him. And what’s more, there’s no way to tell Mikey that he knows what he’s doing without risking death. He silently eats his crackers and sips his beer before getting anxious and antsy. If Mikey is going to run down the clock on Nicky’s life, effectively ending their friendship, it’s in Nicky’s best interest to extend his remaining time by ambling the night away, alternatively changing his mind about what he wants to do before he skips town. (He wants to go to the all-night movie theater to catch the martial arts double feature; no, wait, he has to visit his mistress. Well, shouldn’t he say goodbye to his estranged wife?)

One of the stops Mikey and Nicky make is to the cemetery where Nicky’s mother is buried to pay their respects and effectively say goodbye to her. After locating her grave, Mikey begins to reverently recite the Kaddish; Nicky cracks jokes (“It’s hard to talk to a dead person—nothing in common”). The conversation turns serious when Nicky wishes out loud that his parents were alive, that Mikey’s parents were alive, and that Mikey’s little brother, Izzy—who died when they were children—was also alive. This sparks something in Mikey: A kind of fascination that Nicky, who has frustrated Mikey to wit’s end for years, remembers going to Izzy’s funeral.

May’s sparse filmmaking style for Mikey and Nicky is utilitarian in purpose, providing the space for these two men to feel all the ugly emotions that only closeness over an extended period of time can create.2 May is almost a documentarian, keeping an even-keeled tempo when the film could so easily spin out into a fast-paced thriller; she lets the camera roll for much longer than the scene actually requires, and it’s in this extension that Cassavetes and Falk are able to explore their characters, pulling out the pettiest complaints.

Eventually, we are made privy to the grievances against Nicky that are sticking in Mikey’s craw: Abandonment. Embarrassment. Belittlement. Mikey feels that he’s given Nicky everything by making the introduction to his boss. And now? Nicky won’t even call him back. And when they’re in the same room, Nicky ignores Mikey and jokes about him with their coworkers. He doesn’t have the time for him, even after Mikey paved the way for him. Mikey gets frustrated as he tries to tell Nicky just how deeply Nicky’s abandonment has hurt him. Nicky laughs it off or explains it away, countering that Mikey hasn’t called him in months. Frustrated, Mikey responds that after months of being left on hold, he decided to stop calling. Time has only exacerbated their problems.

This is when the film most reminds me of the ugliness of Swift’s “Bad Blood.” It’s one of those immediate, ruthless fights between longtime friends that’s all subtextual: Time has put physical and temporal distance between the two, and that distance cannot be bridged. In addition to the trappings of time, Mikey and Nicky have the additional wrinkle of traditional masculinity that does not make room for vulnerability, putting the two friends in competition with one another. Now that they’re fighting in the streets, it’s hard to believe that these are the same friends who tenderly held each other in a hotel room earlier in the evening.

During their fight, Nicky throws Mikey’s watch—a gift from his deceased father—to the ground, irreparably breaking it. The bridge that time built is also shattered. To Mikey, it shows that Nicky is completely uninterested in him in a real way. He only sees him as a person who can help him out of a scrape, who can give him entrée to lucrative jobs. Mikey’s presence reminds Nicky of their childhood, and he still treats Mikey like an embarrassing friend he can’t shake; as if to be seen as important to, and be taken seriously by, their gangster colleagues, Nicky has to slough Mikey off. Their childhood closeness no longer exists.

For most of the film, May is filming in the New Hollywood, cinéma vérité style. The camerawork is more documentarian in nature. The style switches near the end—when we are in Mikey’s home, as he recounts the story of his little brother’s childhood death to his wife, Annie—becoming more formal and removed in nature. May is careful to frame Mikey and Annie in such a way that leaves physical distance between the two actors and ample negative space in the shot. For a film that has up to this point been informal, the switch in filming style is noticeable and important. Mikey has spent the whole film holding his close, mature relationship with Annie over Nicky’s head; he chides Nicky, “I don’t treat my wife like you do. When I’m going to be late, I call.” But as Annie halfheartedly engages with Mikey’s story about his brother’s death, something clicks for him. Annie isn’t able to understand him in the same way that Nicky can; there’s a distance (physically in the frame and emotionally in her responses) between them due to her absence in his childhood. To understand Mikey is to understand his past, to understand why he seeks outside approval—from his father, from his bosses, from Nicky.

Mikey and Nicky concludes with Nicky’s inevitable death—shot to death on Mikey’s front porch after pleading for Mikey to let him in (in a reversal of the film’s opening scenes). In the spanse of twelve hours, both men have lost everything. Mikey’s shell-shocked expression upon Nicky’s death, the final shot in May’s film, tipping the film over from dark comedy to tragedy, is the emotional lynchpin. No one will ever truly know him in the same way again. In being complicit in ending Nicky’s life, he’s also cut himself off from his past. Congratulations, you betrayed yourself.

May’s film asks us to consider how betrayal is further complicated by time. Roughly following a 12-hour time period, Mikey and Nicky oscillates between urgency and non-urgency, love and rage. So much can be stuffed into a lifelong friendship, making the betrayal hurt all the worse. Maybe Taylor Swift was wrong in her lyrical assessment of her friendship in “Bad Blood.” Time didn’t—and in all likelihood couldn’t—heal Mikey and Nicky. While it temporarily brought them together, it was ultimately their undoing.

* * *

1. Michael (Mikey) and Nicholas (Nicky) are Peter Falk and John Cassavetes’s real-life middle names, respectively. I swoon every time I think about this.

2. I’d be remiss to not mention Paramount’s issues with Elaine May on this film. May’s exacting vision for the project pushed its production schedule over time, and in order to maintain creative control on the editing of the movie, she had footage smuggled out of the studio. A legal battle between May and Paramount ensued, giving May the reputation for being “difficult.” This unfortunately compromised her career. She directed only one other film, 1987’s Ishtar. Nathan Rabin covers this in more detail in his Criterion Collection essay “Difficult Men.”