In the 1975 film Picnic at Hanging Rock, three private school girls and their teacher disappear during a class trip to the titular rock formation. The rest of the film obsesses about just one of them: ethereal blond Miranda (Anne-Louise Lambert), whose vaguely dreamy charisma has made her the school’s unlikely alpha. Late in the film, one of the others is miraculously found, but rather than reacting with relief, everyone reacts with uniform disappointment that it is not Miranda; apparently, it would be better for no one to be found than for a non-Miranda to return. Lambert’s character appears in a small percentage of the film’s runtime, but we are invited along with those left behind to brood over where this dreamy, doomed girl wound up.

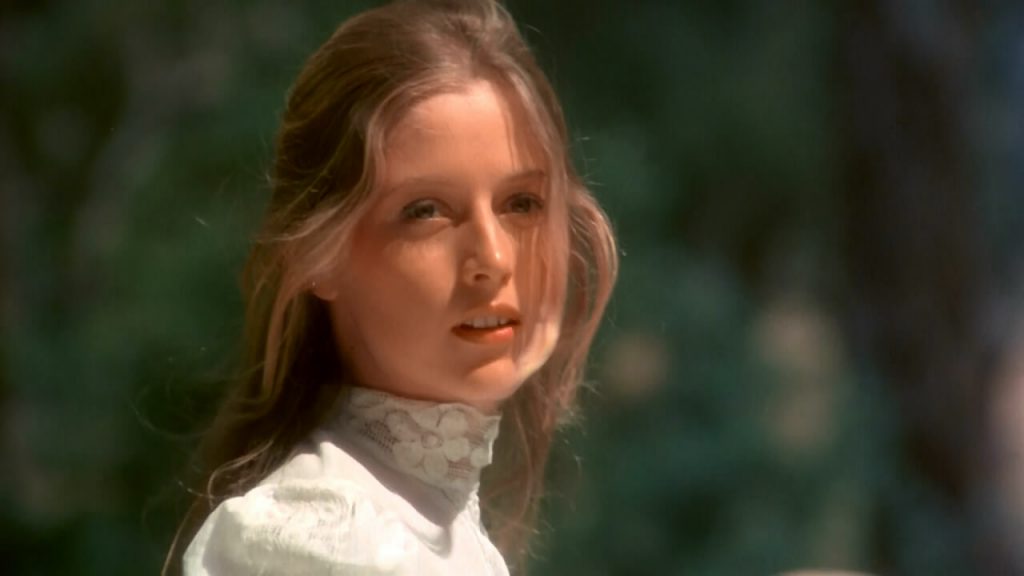

We first meet Miranda in a scene with her worshipful classmate Sara (Margaret Nelson) as she gently warns her friend that she may not always be around. Post-disappearance, Sara sleeps with a makeshift Miranda altar in her bed, and everyone who ever saw her — even those who never knew her name — becomes obsessed with solving the mystery of her disappearance. She wasn’t a femme fatale in the traditional sense – more of an Audrey Horne than a Laura Palmer, all insouciant ennui. One gets the sense she may have disappeared on the rock formation through sheer lack of motivation to leave. Both Lambert’s performance and the extreme mourning exhibited by those left behind invite the audience to join in this shared obsession, and director Peter Weir enables our obsession too, intercutting the film with sunny, gorgeous flashbacks to Miranda’s lovely, blank face.

A more contemporary cult of adoration currently exists for the tonally similar 1991 film, The Virgin Suicides. Sofia Coppola’s debut feature single-handedly launched the still-popular Instagram aesthetic of sunny sepia filters on gauzy, girlie imagery. As in Picnic at Hanging Rock, the crux of this film lies in Kirsten Dunst’s gloriously shot role of teenage Lux Lisbon, a protagonist by proxy as we learn her story by way of an unnamed male narrator, one of the gang of boys who obsessed over her in life and later in death. This film contains a sequence in which the boys imagine Lux and her sisters lazing wholesomely in a sunny field of grass and flowers, at once a part of the natural beauty and the most beautiful part of it. Miranda’s admirers in Picnic at Hanging Rock also imagine their icon in a similar manner; both sequences highlight that we’re seeing the stories not of these girls themselves, but of how others dreamed of them. But while the community in Picnic at Hanging Rock is all but ruined by Miranda’s disappearance, the Virgin Suicides boys – even in adulthood – seem to still think that dying was the coolest thing Lux ever did.

A counterpoint to these two girls is Elle Fanning’s Alicia in Coppola’s latest film, The Beguiled (2017). Similar in attitude to the others, Alicia slumps and drapes her way around a mostly-abandoned Civil War-era school, emanating the world-weary cynicism of a girl who’s never really done anything. Where Miranda and Lux’s biggest life decisions are to disappear or to die, surprising twists in their seemingly otherwise blasé lives, Alicia is one of her film’s main protagonists, and as such, has more agency over her situation. If she’d grown up in the Lisbon household or been trapped in Appleyard College in Australia, perhaps she would have wound up like the others. But she’s in Miss Farnsworth’s (Nicole Kidman) school in The Beguiled and finds adventure right on her doorstep with the arrival of injured soldier John McBurney (Colin Farrell). True to form, her first instinct at seeing him is not to cower or to gasp but basically to purr, finding in him an outlet for all of her pent-up moodiness, his attention a meaningful way to show herself as more special than the others in her school. Yet, other than her interactions with John, her entire self emanates ennui, the feeling that is a part of many girls’ adolescence, the sense of being on the precipice of something exciting but having to wait for life to catch up with you.

These three films shoot their female characters beautifully – all soft focus and floaty dresses and dewy-eyed looks. This style is wielded purposefully as a counterpoint to each film’s core of the ferocious and often unpredictable rage that can flow inside even the most seemingly docile young women. In one scene in Picnic at Hanging Rock, the girls turn on one of their own, feral as in The Handmaid’s Tale‘s scenes of reckoning. In The Virgin Suicides, Lux screams and wails when her mother destroys her record collection; and, of course, the final act of The Beguiled involves the women and girls plotting murder. The contrast of style and content not only provides for satisfying tension, but also serves as a metaphor for how in life, too, the accoutrements of femininity are wielded in a similar way – the surprise when we realize the amount of rage percolating not in the tattooed and pierced punks but in the softest, quietest girls. This is because of our traditional understanding that male rage is performative, revealing itself in fight clubs and school shootings, while female rage turns inward, to self-harm and eating disorders and anxiety.

When Miranda and her classmates set out for their fateful Valentine’s Day field trip to Hanging Rock, they are each dressed up like dolls in white lacy dresses, hats, and gloves. Because it’s a hot day, Mrs. Appleyard (Rachel Roberts) grants them permission to remove their gloves – but only once they’re passed through a nearby town, lest the young men there spy an inch of girlish finger. The image of this school, surrounded entirely by vicious nature (both venomous snakes and poisonous ants are name-checked) is a similar metaphorical setting as The Beguiled‘s school being surrounded at all sides by war. Only kept inside – behind windows and doors, laced into corsets, necklines buttoned high – can these girls be restrained. And to Miranda, glove removal seems to be the first step toward a hike to the top of Hanging Rock, which leads to the removal of her shoes, stockings, and eventually corset. To a teenage girl of any time period, this sartorial statement – and the blissed-out dancing and twirling that ensues – could not be a more clear statement of independence from patriarchal conventions and expectations of femininity. And yet, shortly after this moment of freedom, she disappears.

Similarly, both Alicia and Lux find themselves in trouble for their most notable acts of rebellion – in both cases, that of having sex. While Lux, unapologetic, is punished for her behaviour with a house arrest that turns into captivity, Alicia instantly apologizes, recasting herself as a victim, falling into line with the others. Still, each situation is a razor’s edge away from a morality tale, a warning to young women that any mistake could be irreversible, so it’s best to never challenge the status quo. And yet, it’s in their undoing that each girl firmly establishes herself as an icon of terrifying and beautiful teen girl magic. When McBurney arrives at Farnsworth’s school, he is beguiled by its simulacrum of an oasis – all pale colours and soft-spoken blond women, the overgrown garden not a symptom of decay but, like in Sleeping Beauty, of something beautiful that needs to be saved. And indeed, he quickly offers his services to tend to this garden, taming its wild vines into something prettier, more manageable. Because after all, a group of women and girls are surely in need of a man. But the thing is, they aren’t, no more than the girls in Hanging Rock or The Virgin Suicides were, and that’s precisely what makes them so magical to young girls and so terrifying to the men who encounter them.

Strand a group of teenage boys on their own and you get Lord of the Flies; mix boys and girls and it’s Battle Royale or The Hunger Games. Each situation finds the teens roleplaying a Bugsy Malone version of the world with which they’re familiar, the richest and most heartless boys always at the top of the food chain. But when girls and women are shown on their own, without the influence of a male figure, the result is much more open-ended because there is no room for them in the world outside. Girls left alone, separated not only from other genders but from the world at large, create their own ecosystem that doesn’t mirror the real world so much as suggests one of their own. In these covens or hives, men may see the women and girls as unstable or in need of saving; but to girls, these miniature societies may look like the perfect escape.

Of course, the time the Lisbon girls spent trapped in their home was the low point of an already-depressing year. But to us, and to the boys who spied on them from across the street, it’s the most Instagram-perfect slumber party of all time – the girls laying around roller-skate cool in tube tops and knee socks, listening to records, like a four-person 1970s remake of Sleeping Beauty. And indeed, the boys see themselves as the girls’ saviours, right up until they arrive to find them already all dead. Rage and darkness masked by pretty fantasies of pretty girls; the final coda of this film is its most gutting twist. Because we’d seen scenes without the boys, it’s easy to forget we’re seeing this story entirely through their memories. Irma (Karen Robson), the only survivor to return from Hanging Rock, convalesces in a dormitory room with mosquito netting hung up like a canopy bed, her dark hair and pale skin recalling another famous passive fairytale princess. She never reveals what happened to Miranda that day on the rock, and has the luck to be transferred away from Appleyard College just before things turn truly grim. But in The Beguiled, our fairytale heroines survive their encounter with McBurney because, as protagonists, they have the room to exhibit more than a fairytale shorthand of personality. It is only in this film, with Alicia and the others driving the narrative, that these girls and women are able to act; Lux and Miranda, by virtue of their circumstances, may only react. So while Lux chooses to die and Miranda makes herself disappear, Alicia turns her overabundance of life energy toward seducing McBurney, a plan that begins with kissing him as he sleeps – turning the gaze, in that moment, from her to him, claiming him as her conquest.

The final scene of The Beguiled frames the girls and teachers, safely again behind their wrought iron fence, Alicia’s hands two of many working diligently to sew up McBurney’s body bag. But then, the camera turns, and we see her teacher Edwina, played by a now 30-something Dunst, herself gazing off in the middle distance in a manner reminiscent of Alicia in the film’s opening. Edwina’s dress is tightly buttoned to the neck, hair tucked away, having completed her maturation from wise sad teen to wise sad woman, but it’s a whole different brand of sadness, one understandably less appealing to the teens who still pay tribute to her Lux on Tumblr and Instagram. The Lisbon sisters each included Catholic iconography in their stunning dresser and vanity collages, similar iconography to that now used to pay homage to Lux herself, a sort of patron saint of teen girl rage.